Each year, during the start of school, teachers and administrators try to explain to new parents the essence of the term Montessori. In this article, we’ll try to explain what Montessori is and is not, dispelling, we hope, a few misperceptions about Montessori education in the process.

In its simplest form, Montessori is the philosophy of child and human development as presented by Dr. Maria Montessori, an Italian physician who lived from 1870 to 1952.

In the early 1900s, Dr. Montessori built her work with mentally challenged children on the research and studies of Jean Itard (1774-1838), best known for his work with the “Wild Boy of Aveyron” and Edward Seguin (1821-1882), who expanded Itard’s work with deaf children. In 1907, Dr. Montessori began using her teaching materials with normal children in a Rome tenement and discovered what she called “the Secret of Childhood.”

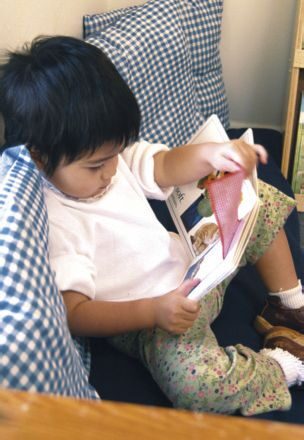

The secret? Children love to be involved in self-directed purposeful activities. When given a prepared environment of meaningful projects, along with the time to do those tasks at his or her own pace, a child will choose to engage in activities that will create learning in personal and powerful ways.

Over the past one hundred years, Montessori classrooms all over the world have proven that, when correctly implemented, Dr. Montessori’s philosophy works for children of all socioeconomic circumstances and all levels of ability. In a properly prepared Montessori classroom, research shows that children learn faster and more easily than in traditional schools.

However, the implementation of Montessori philosophy is a school’s biggest challenge. There are many factors to consider when putting theory into practice: the individual children in the classroom, their ages and emotional well-being; parent support and understanding of Montessori philosophy; and the training and experience of teachers, assistants, and administrators. These are only a few of the elements that create a Montessori school.

Because of this, Montessori schools come in all shapes and sizes, including the small in-home class for a few children to schools with hundreds of students, from newborns through high school.

While schools come in many shapes and sizes, all successful Montessori classrooms require three key elements:

1. Well-trained adults;

2. Specially prepared environments; and

3. Children’s free choice of activity within a three-hour work cycle.

Finding the right school for your family – whether it’s Montessori, public, parochial, alternative, traditional, or home school – requires a bit of investigative work and an understanding of the needs and concerns you have for your family. Being clear about what Montessori education is and what it is not can help you make an informed decision.

In my thirty years in Montessori education – as a parent, school employee, volunteer, trainee, teacher, school founder, and school director – time after time, I’ve come to fresh and deeper understandings of Montessori philosophy and the process of human development and education.

My first encounter with Montessori was less than positive. As a college student, I frequently visited my family after my four younger siblings’ school day had ended. Our family tradition was to have a snack together after school. Friends and neighbors were always welcomed.

The neighbor girls (ages four, five and six) frequently joined the group. They would barge into my parents’ home and head straight for the refrigerator. No knock on the door, no hello. They inhaled huge amounts of food with neither manners nor thanks. Their lack of decorum appalled me.

The neighbor girls’ grandmother chatted with me about how wonderful the girls’ Montessori school was and how much the girls learned there. I attributed the girls’ little savage conduct to their Montessori school. If a school would put up with that kind of behavior, I figured it couldn’t be any good.

A few years passed, and I had children of my own. Our friends and co-workers recommended the local Montessori school to my husband and me. Because of my experiences with the neighbor’s children, I responded negatively to my friends’ suggestions. I began to notice, though, that our friends’ children were well mannered, articulate, and a joy to be around. Hum? So what was up with Montessori?

My mother helped clear up my misperceptions. The neighbor’s girls, even though they lived in an expensive home, were suffering the effects of a newly divorced and stressed mother attending law school. The girls were starved for food, attention, and adult guidance. Their behavior was a reflection, not of their Montessori schooling, but of the turmoil in their home.

This experience showed me that what we may think are the effects, negative or positive, of a Montessori school, may be something quite different.

Let me use my thirty years of Montessori experience to help dispel a few misconceptions about Montessori schools, some of which I’ve held myself.

Myth #1 – Montessori is just for rich kids.

Many Montessori schools in the United States are private schools, begun in the early to mid-1960s, a time when most public education didn’t offer kindergarten and only 5 percent of children went to preschool, compared with the 67 percent reported in the 2000 census.

When many Montessori schools were established, private preschools might have been an option only for those in urban well-to-do areas, thus giving the impression that only wealthy families could afford Montessori schools.The first schools that Montessori established were in the slums of Rome, for children left at home while parents were out working, and certainly not for rich kids.

Today, in the United States, there are over 500 publicly funded Montessori schools, along with thousands of private, not-for-profit Montessori programs that use charitable donations to offer low-cost tuition.

Montessori education, through these low-cost options, is available to families interested in quality education. Many private, high-dollar schools offer scholarships, and some states offer childcare credits and assistance to low-income families.

Myth #2 – Montessori is just for gifted kids.

Montessori is for all children. Since Montessori preschools begin working with three-year-olds in a prepared learning environment, Montessori students learn to read, write, and understand the world around them in ways that they can easily express. To the casual observer, Montessori students may appear advanced for their age, leading to the assumption that the schools cater to gifted children.

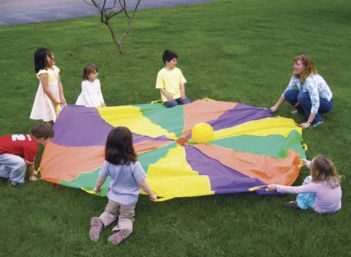

In reality, a Montessori school offers children of differing abilities ways to express their unique personalities, through activities using handson materials, language, numbers, art, music, movement, and more. Montessori schooling helps each child develop individuality in a way that accentuates his or her innate intelligence. Montessori schools can help make all kids ‘gifted’ kids.

Myth #3 – Montessori is for learning-disabled children.

It is true that Dr. Montessori began her work with children who were institutionalized, due to physical or mental impairments. When using her methods and materials with normal children, Montessori discovered that children learned more quickly using her teaching methods.

There are some Montessori schools and programs that cater specifically to children who have learning challenges. In many Montessori schools, however, children with special needs are included, when those requirements can be met with existing school resources.

Myth #4 – Montessori is affiliated with the Catholic Church.

Like many preschools, some Montessori programs may be sponsored by a church or synagogue, but most Montessori schools are established as independent entities. Conversely, a school might be housed in a church building and not have any religious affiliation. Since Montessori refers to a philosophy, and not an organization, schools are free to have relationships with other organizations, including churches.

Some of the first Montessori programs were sponsored by Catholic or other religious organizations. Dr. Montessori was Catholic and worked on developing religious, educational, hands-on learning experiences for young children. The Montessori movement, however, has no religious affiliations.

Montessori schools all over the world reflect the specific values and beliefs of the staff members and families that form each school community. Around the world, there are Montessori schools that are part of Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and other religious communities.

Myth # 5 In Montessori classrooms, children run around and do whatever they want.

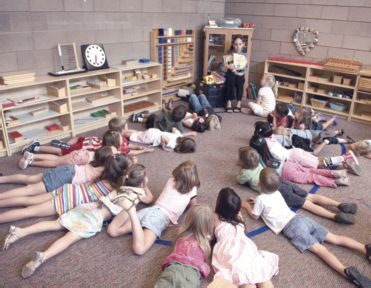

When looking at a Montessori classroom you may see twenty-five or more children involved in individual or small group activities. It is possible that each child will be doing something different. At first glance, a classroom can look like a hive of bumblebees.

If you take the time to follow the activities of two children over the course of a three-hour work period, you should observe a series of self-directed activities. The children aren’t running wild. They are each involved in selfselected work, designed to build concentration and support independent learning.

Choosing what you do is not the same as doing whatever you want. A wellknown anecdote about Montessori students doing what they like, comes from E.M. Standing’s book, Maria Montessori – Her Life and Work: “A rather captious and skeptical visitor to a Montessori class once buttonholed one of the children – a little girl of seven – and asked: ‘Is it true that in this school you are allowed to do anything you like?’ ‘I don’t know about that,’ replied the little maiden cautiously, ‘but I do know that we like what we do!’”

Myth #6 – Montessorians are a selective clique.

One definition of a clique is: an exclusive circle of people with a common purpose. Many Montessori teachers could be accused of this because of their intense desire to be of service in the life of a child, coupled with the teacher’s knowledge of child development. While many schools have tightknit communities, they are not exclusive. You should look for a school where you and your family feel welcomed.

For many years, Montessori training programs were only available in a few larger cities. Becoming certified required prospective teachers to be determined and dedicated, as relocating for a year of study was often required. Now, Montessori teacher training is mainstream and more accessible, with colleges and universities offering graduate programs in Montessori education in conjunction with Montessori training centers.

Dr. Montessori’s books, full of Italian scientific and psychological terminology, translated into the British English of the early 1990s, can be difficult for the modern reader to follow. To parents, the use of Montessori-specific terms and quotes may at times take on esoteric tones of an elusive inner circle.

The enthusiasm and dedication evident in the work of many Montessorians might be misinterpreted as excluding to uninitiated newcomers. My experience with Montessori teachers and administrators has been that they are eager to share their knowledge with others. Just ask!

Myth #7 – Montessori classrooms are too structured.

Parents sometimes see the Montessori concept of work as play as overly structured. The activities in the classroom are referred to as work, and the children are directed to choose their work. However, the children’s work is very satisfying to them, and they make no distinction between work and play. Children almost always find Montessori activities both interesting and fun.

Each Montessori classroom is lined with low shelves filled with materials. The teacher, or guide, shows the children how to use the materials by giving individual lessons. The child is shown a specific way to use the materials but is allowed to explore them by using them in a variety of ways, with the only limitations being that materials may not be abused or used to harm others.

For example, the Red Rods, which are a set of ten painted wooden rods up to a meter long and about an inch thick, are designed to help the child learn to perceive length in 10 centimeter increments. The Red Rods aren’t to be used as Jedi light sabers. Obviously, sword fights with the Red Rods are a danger to other children, as well as damaging to the rods.

In cases where materials are being abused or used in a way that may hurt others, the child is stopped and gently and kindly redirected to other work. Unfortunately, some parents see this limitation on the use of the material as ‘too structured,’ since it may not allow for fantasy play.

Myth #8- A Montessori classroom is too unstructured for my child.

The Montessori classroom is very structured, but that structure is quite different from a traditional preschool. Montessori observed that children naturally tend to use self-selected, purposeful activities to develop themselves. The Montessori classroom, with its prepared activities and trained adults, is structured to promote this natural process of human development.

Students new to the Montessori classroom, who may or may not have been in a traditionally structured school, learn to select their own work and complete it with order, concentration, and attention to detail. Montessorians refer to children, who work in this independent, self-disciplined way as ‘normalized,’ or using the natural and normal tendencies of human development.

Many traditional preschools work on a schedule where the entire classroom is involved in an activity for 15 minutes, then moves on to the next activity. This structure is based on the belief that young children have a short attention span of less than 20 minutes per activity.

“The children of different ages in the school help one another. There is communication and harmony. Older ones become teachers and heroes to the younger children. The little ones sense that when they are bigger their turn will come.” – Maria Montessori

Myth #9 – Montessori schools don’t allow for play.

Montessorians refer to the child’s activities in the classroom as work. The children also refer to what they do in the classroom as their work. When your three-year-old comes home from school talking about the work he did today, he can sound way too serious for a kid you just picked up at preschool.

What adults often forget is that children have a deep desire to contribute meaningfully, which we deny when we regard everything they do as ‘just’ play. With our adult eyes, we can observe the child’s ‘joyful work’ and expressions of deep satisfaction as the child experiences ‘work as play.’

Consider this. You start a new job. You arrive on the first day, full of enthusiasm, and ready to contribute to the success of your work group. You’re met at the door by your new boss and told, “Go outside and play. We’ll let you know when it’s time for lunch and time to go home.” Ouch!

But that’s exactly what we do to our children when we dismiss their desires to contribute to their own well-being and to the common good of home or school. Montessori schools create environments, where children enjoy working on activities with grace and dignity. Montessori children often describe feelings of satisfaction and exhilaration upon completing tasks that we might have considered as only ‘play.’

Myth #10 – Montessori doesn’t allow for creativity.

Creativity means “to bring something into existence.” First we have an idea. Then we use our imagination, thoughts, and skills to bring these ideas into being. The Montessori classroom nourishes the creative skills of writing, drawing, painting, using scissors, modeling clay, gluing, etc. to enable children to express their thoughts and ideas in genuine and unique ways.

When I was in kindergarten, we were all given a coloring sheet of a caboose. I colored my caboose green. My teacher told me that cabooses were red. As I looked around, all the other children’s cabooses were red. My classmates laughed at my green caboose. I felt the tears in my chest.

Twenty-four years later, I saw another green caboose, attached to the end of a Burlington-Northern train. “Yes!” I wanted to shout back to my kindergarten class. “There are green cabooses.”

What does a green caboose have to do with creativity? I wasn’t trying to be creative with my green caboose. I was trying to express myself, because I had seen a green caboose.

Montessori classrooms allow for safe self-expression through art, music, movement, and manipulation of materials and can be one of the most creative and satisfying environments for a child to learn to experiment and express his or her inner-self.

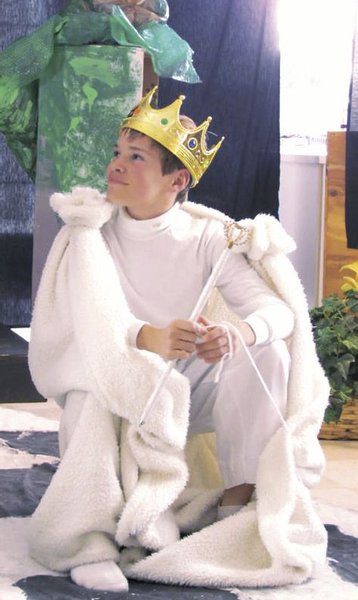

Myth #11 – Kids can’t be kids in Montessori.

Somehow, our expectations as parents, having witnessed temper tantrums in restaurants and stores, create a view of children as naturally loud, prone to violent behavior, disrespectful of others, clumsy, and worse.

In a well-run Montessori classroom, though, one might be tempted to think that kids aren’t being kids. When you see twenty-five to thirty children acting purposefully, walking calmly, talking in low voices to each other, carrying glass objects, reading and working with numbers in the thousands, you might think the only way this behavior can occur is by children being regimented into it. I remember observing Dana (then fifteen-months-old), moving serenely around her infant Montessori classroom. She sure didn’t act that way at home.

As I observed Dana’s infant-toddler class in action, I saw the power of this child-friendly environment. As the children moved from activity to activity, day by day their skills and confidence grew. Lessons in grace and courtesy helped the children with social skills, as please, thank you, and would you please became some of these toddlers’ first words.

When Dana was three, one of her favorite activities was the green bean cutting lesson. After carefully washing her hands, she would take several green beans out of the refrigerator, wash them, cut them into bite-sized pieces with a small knife, and arrange them on a childsized tray. She carried the tray around the classroom, asking her classmates, “Would you like a green bean?” As they looked up from their work, the other children would reply: Yes, please, or No, thank you.

Dana, now an adult, still remembers that work with deep satisfaction. Children show us (when given a prepared environment, a knowledgeable adult, and a three-hour work cycle) that the natural state of the child is to be a happy, considerate, and contented person. A child is most like a child when he or she is engaged in the work of the Montessori classroom.

Myth #12 – If Montessori is so great, why aren’t former students better known?

Most of us associate our career success with our colleges. Not too many people come out and say, “When I was three years old I went to Hometown Montessori School, and that made all the difference.”

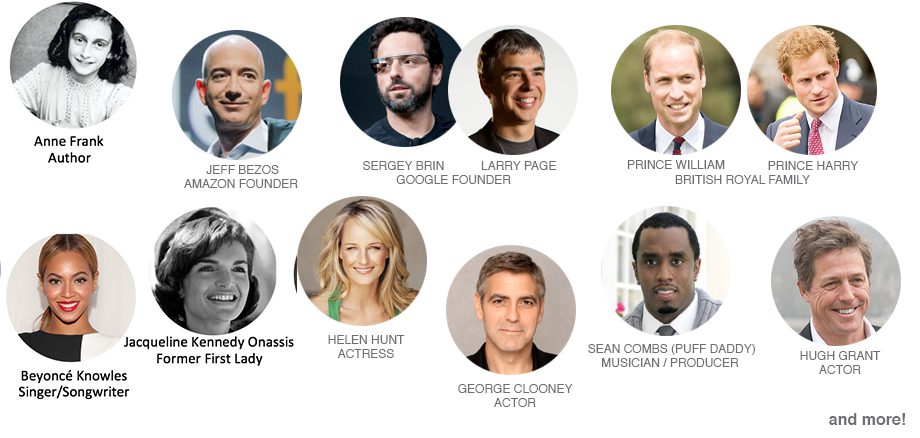

Here are a few well-known people who remember their Montessori school connections and consider their experiences there vital.

Julia Child, the cook and writer, who taught Americans to love, prepare and pronounce French dishes, attended Montessori school.

Peter Drucker, the business guru, who has been said to be one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century, was a Montessori student.

Alice Waters, the chef of Chéz Panisse fame and creator of The Edible Schoolyard project, was a Montessori teacher.

Anne Frank’s famous diary was a natural extension of Anne’s Montessori elementary school experience.

Annie Sullivan, Helen Keller’s teacher, corresponded with Maria Montessori about teaching methods.

Larry Page and Sergei Brin, founders of Google, Jeff Bezos founder of Amazon, and Steve Case of America Online all credit Montessori schooling to their creative success.

Montessori schools are focused on helping children become self-directed individuals, who can, and do, make a difference in their families, in their communities, and in their world – famous or not. And that’s not a myth.

Maren Stark-Schmidt, an award-winning teacher and writer, founded a Montessori school and holds a Masters of Education from Loyola College in Maryland. She has over 30 years experience working with young children and holds teaching credentials from the Association Montessori Internationale.

She currently writes a syndicated parenting column, available at http://www.KidsTalkNews.com and is the author of Understanding Montessori: A Guide For Parents, and Building Cathedrals Not Walls. Contact her at maren_schmidt@me.com and visit http://MarenSchmidt.com. Copyright 2012. Reprinted with permission.